Sight and Sound recently ran a feature in praise of cinematographers, and suggesting that few could really be called household names. One name which might spring more readily to mind than others is Jack Cardiff, and for good reason.

Sight and Sound recently ran a feature in praise of cinematographers, and suggesting that few could really be called household names. One name which might spring more readily to mind than others is Jack Cardiff, and for good reason.

Several good reasons in fact, most significantly a trio of films which he shot for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger starting with the startling kaleidoscopic visions (in colour and black and white) of A Matter Of Life and Death (1946), continuing with the stunning (false) Himalayan sweep of Black Narcissus (1947), and finishing with the ravishing colourful flourish of The Red Shoes (1948).

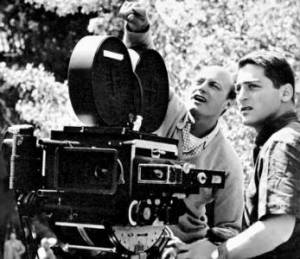

These three films not only sealed Powell and Pressburger’s reputations but so too Cardiff’s, who then became cinematographer to the stars, shooting subsequently for the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, John Huston and Laurence Olivier, as well as intermittently turning his hand to direction himself.

The Powell/Pressburger films stand as his testament. All three remarkable for their use of Technicolour, but also in very different ways from each other: the fluid dynamism of The Red Shoes, the stately elegance and breathtaking scale of Black Narcissus, and the sheer visual wizardry of the range of visual tricks in Life and Death show a visual artist with an incomparably complete mastery of the camera. Marilyn Monroe described him as ‘the best in the world’. It is hard to argue against this.