21 JUMP STREET (B+) Amiability marred by misplaced crassness, but smart & witty throughout, reflexively subverting teen movie tropes with aplomb

ALPS (C+) Lanthimos’ rigorous sphere of morbid social dysfunction here feels an admirable folly; reflexivity mildly enlivens lethargy

AMOUR (B+/A-) Humanity, and Haneke, stripped bare. Unfliching, insidiously horrifying, unimpeachably performed, tho restraint borders on passivity

THE AVENGERS (A-) Assembly instructions: slot sub-franchises [B]-[E] into film [A]; glue together with wit, warmth & visual flair. Nailed it.

BARBARA (A) Profoundly moral yet never pedagogic and, unlike ‘Others’, oppression by gesture& suggestion powerfully, insidiously devastating

BEASTS OF THE SOUTHERN WILD (B-) Strikingly hermetic, appropriately ramshackle world-building, muscularity drowning out creaky Malickisms

BERBERIAN SOUND STUDIO (A-) Warm, affectionate meta-cinematic glow dissolves into Polanskian purgatory between reality & art. Mesmerizing.

BOMBAY BEACH (B+/A-) The messy underweave of the American social tapestry. Visually elegant, disarmingly non-judgemental, quietly remarkable

CABIN IN THE WOODS (B+) A cellarful of meta-chuckles, though setup leaves some awkward problems which the script only partially resolves

CARNAGE (C+) Fizzingly acrid chamber farce a shoo-in for the arch misanthrope Polanski, but as cine spectacle becomes increasingly wearisome

CHRONICLE (B+) Found footage gripes aside, a relentlessly entertaining tranchette of teen super-hijinks, flying while grounded in reality

COCKNEYS VS ZOMBIES (C-) Handful of decent gags keeps things just the right side of amiable, though in too many depts more than a bit ‘pony’

A DANGEROUS METHOD (C-) A welcome mischief sometimes undercuts semi-serious façade, but ideas too inchoate, central conflict too stagnant

THE DARK KNIGHT RISES (B+) Most satisfying of the three: a thrilling leap, inadequate only in terms of its own (impossibly?) lofty ambitions

DREDD (C-) Nails its heads-a-poppin’ aesthetic, but script, narrative and scope naggingly unsatisfying, carrying the air of a TV series pilot

ELENA (A-) Pulsating, fastidious ice-cold noir & dissection of Russian society, elegantly camouflaged beneath surface of glacial mundanity

THE GIANTS (B-) Beguiling hard edged boys own fantasy; freewheeling/lackadaisical (to taste), unassumingly génial, delightfully performed

GRABBERS (B-) Hugely endearing Irish small town creature feature, delicately genre savvy & a great paean to the joys of getting pissed

THE GREY (D+) Marooned between existential hardship drama and creature feature, sadly unwilling to acknowledge own crescendoing silliness

LE HAVRE (B+) More colourful comings-and-goings in Akiland, with a dash of Pierre Etaix & a warmth which embraces like a salty sea breeze

HOLY MOTORS (A-), or “Faces Without an I”? Barmy mélange of cine amuses-bouches, deftly juggling notions of performance, spectacle & self

THE INNKEEPERS (A-) Smartly keeps its scares rooted in the subjective, but it’s the warm, endearing characters which persist in the memory

INTO THE ABYSS (B-/C+) Compelling subject matter, grand themes, but strangely feels a minor Herzog: too much respect, not enough Werner

IRON SKY (F) Limited resources no excuse for this level of all-round incompetence. Concept shorn of laughs, satire already horribly dated

ISN’T ANYONE ALIVE (C-/D+) Playful anti-genre mischief surgically undercuts apocalypse expectations & pathos; fleetingly amusing but jejeune

JOHN CARTER (B+) Derivative, yes, but still hugely enjoyable romping fare, directed with storytelling nous & wit. Who cares how much it cost?

THE KID WITH A BIKE (B-) Brightly-hued, dark-edged fairytale, landing between Bresson & De Sica. Energetic, but nagglingly Dardennes-lite

LAWLESS (D+) Aimless, listless jumble of incongruities. Rompishness amuses but never stirs, punctuated bursts of violence an affectation

LOOPER (C+/B-) Entertaining enough knotty yarn, admirably freewheeling in its storytelling, but overstuffed with billowing, under-developed threads

MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE (C+) Moody, meritorious, meticulous but ultimately meritricious. Fragmentary structure renders material oddly inert

THE MASTER (B+) Eschews straight dialectics for murkier blurs. Enigmatic rope-a-doping deliberately estranges, heavier punches hit hard

MOONRISE KINGDOM (B-) Further variations on familiar themes; younger leads a reinvigoration, partially puncturing shell of meticulousness

NOSTALGIA FOR THE LIGHT (A-) Plaintive, yet wonder-filled meditation on overlap between the corporeal & the cosmic; unpretentious, sublime.

ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA (A-) A sprawling miniature, elegaic & comic; pick as much from the twined contradictions as you wish

OUTPOST: BLACK SUN (D+) Technically adept, if chronically under-lit, but story’s a bore; flavourless characters had me rooting for the Nazis

THE POSSESSION (C+) Polished studio product, no more or less. Ditches early character work for derivative, predictable hokum

PROMETHEUS (B-) An odd beast, jarringly swivelling between the hokey and grandiose, but entertains more & more as it slowly shows its hand

THE QUEEN OF VERSAILLES (B+) Garishly compelling, yet locates pathos & humanity amidst capitalist grotesquery, trumping Inside Job’s didactisism

[REC]³ GENESIS (B-) No idea what, if anything, defines the franchise any more, but this was great, ribald taffeta-clad fun

RUST & BONE (B-) Remain unconvinced by Audiard’s worthy Melotrash material, but performances & corporeal blend of the tender & visceral are stirring

SAMSARA (D+) Yes, a feast for the retinas, but for the brain it’s undernourishing; synthesis of imagery feels cumulatively trite& sophomoric

SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN (C+) After the (cold) fact doc sluggish out of the blocks, though slow reveal eventually yields ANVIL-like poignancy

SEVEN PSYCHOPATHS (D+) Staid, sophomoric meta-ness wearisome, causing gags to fall flat. Outer narrative shell dull cf scripts-within-script

SHAME (C+) Technical virtuosity is dazzling, but wanton meticulousness blunts material. Too much glistening surface, not enough murky depth

SINISTER (B-/C+) Throws its net wide, pecking corn like the metaphorical blind hen, though with surprising frequency. Effective sound, Hawke classy

SWANDOWN (B-) Psychogeographical search for confluence between Herzog & Jerome K Jerome. Fleetingly piquant, but poignancy punctures whimsy

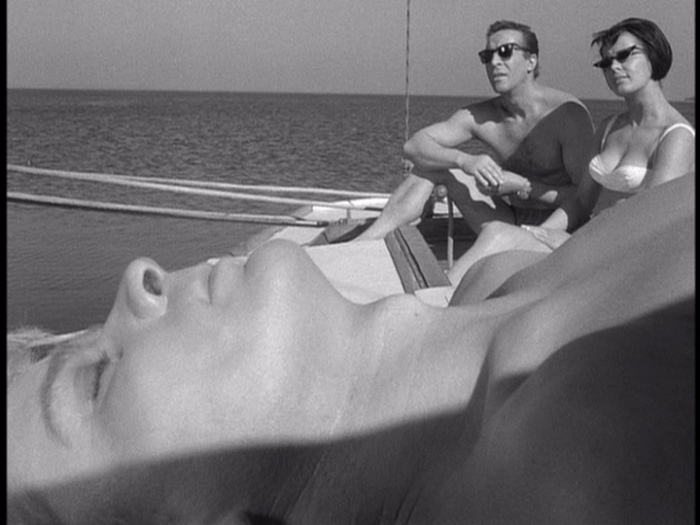

TABU (A) History as memories of a papered-over, near-mythical past. Upshift into swooning reverie of Nerudan yearning a minor miracle

THIS MUST BE THE PLACE (C-) Alice Cooper in the Cities? Penn’s oddball perf a grower; pathos, ideas & momentum all frustratingly staccato

TINY FURNITURE (B-) Hardly revelatory, but ample flashes of drollery & pathos. Painfully well-observed and – crucially – never feels vain

TOWER BLOCK (C+) Frantic LIFEBOAT-meets-Broken-Britain setup, better before moralizing & explanations. Cutaways to gunman a misfire

THE TURIN HORSE (A-) Precise, rhythmic four-beat gait hypnotic, bearing this heaviest of burdens; allegories near-parodic, yet tantalising

W.E. (D-) Lacklustre, ill-conceived, though not the outright catastrophe I expected. Still, a poor man’s Sofia Coppola is a poor man indeed

THE WOMAN IN BLACK (2012, C+) Ornate, serviceable retread. DR can’t hack backstory heft but gleeful relentlessness of jumpy second act a plus

YOUNG ADULT (B+/A-) Smartly reduces bunny-boiling down to a gentle simmer, steaming off credulity but thickening the delicious character darkness